Dr. Fauzia Lone

(The article was published in BBC Urdu)

Today we will try to understand the agreement under which the princely state was annexed to India under the leadership of Maharaja Hari Singh, namely the ‘Instrument of Accession’ of 1947. We will try to understand the background and the circumstances under which it was signed, as well as its legal status in the eyes of the legal experts of the “Foreign Office Legal Advisers”.

Kashmir: An Independent Princely State

Before the partition of British India, Kashmir was an independent princely state under British rule. Not all princely states at that time were considered part of British India, nor did the citizens of these princely states enjoy being considered British Citizens. The British Parliament did not even have the right to legislate for these princely states. Yes, the British authorities had defense and foreign policy powers to them.

The British intervened in Kashmir only when the law and order situation there had deteriorated due to government failures. For example, during the reign of Maharaja Pratap Singh, when his suspicious dealings against the British crown increased, the authorities interfered in the internal politics of Kashmir and removed the Maharaja from power from 1889 to 1905.

Unlike other Indian princely states, there was no permanent British ‘resident’ in Kashmir till 1885 and the reason for the change in policy in 1885 was actually a potential threat from Russia and Afghanistan and not the internal situation of Kashmir.

Overall, Kashmir, being a ‘buffer’ state, enjoyed more autonomy and other political privileges than other princely states. Kashmir had its own constitution, its own laws and agreements with Britain and its neighbors. In the last days of British rule in India, Kashmir’s sovereignty was clearly recognized.

The Question of Partition of British India and Princely States

The first question that arose at the end of British imperialism in India was what would be the relationship between the princely states and these two new countries, India and Pakistan, after the end of British patronage?

The British government had made it clear through a number of statements and laws that the British rule could not be replaced by new countries, India and Pakistan, and that their patronage would end.

The British wanted the princely states to decide for themselves whether they wanted to be part of India or Pakistan or to remain independent. However, these statements often contained indications that British wished the princely states to choose between India and Pakistan.

In the case of Kashmir, the question became even more important as the Maharaja immediately chose sovereignty by refusing to join either of the two new countries.

According to the Government of India Act of 1935, the claims made by the princely states were accepted. Under the Act, it was promised that an independent India would not take precedence over these princely states. That was before the existence of Pakistan was even discussed.

In 1946, the British Cabinet Mission in India stated in a statement that this supremacy “could neither remain with the British crown nor be transferred to a new government.”

This was reiterated in the Cabinet Mission Memorandum issued on 12 May 1946: ‘The rights of the state which are the result of its association with the British Crown will cease to exist. All the rights that the states gave to the British Raj will now go back to the states.

On February 20, 1947, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Clement Attlee, told the British Parliament that the position of the British Government was the same as that of the Cabinet Mission. He also said that “the Queen’s Government of the United Kingdom has no intention of handing over the rights and duties of the British Raj to any Government of India.”

A statement dated June 3, 1947 reiterated that there would be no transfer of powers and duties in the princely states. Then, on July 10, 1947, the Prime Minister Clement Attlee reiterated his position.

On July 16, 1947, Lord Listowel, Minister of State for Indian and Burmese Affairs, stated in the Upper House of the British Parliament: “From this moment, all the Princely States will decide for themselves whether they want to join India or Pakistan or stand alone. Over time, all the princely states must find their rightful place in one of the two new countries”.

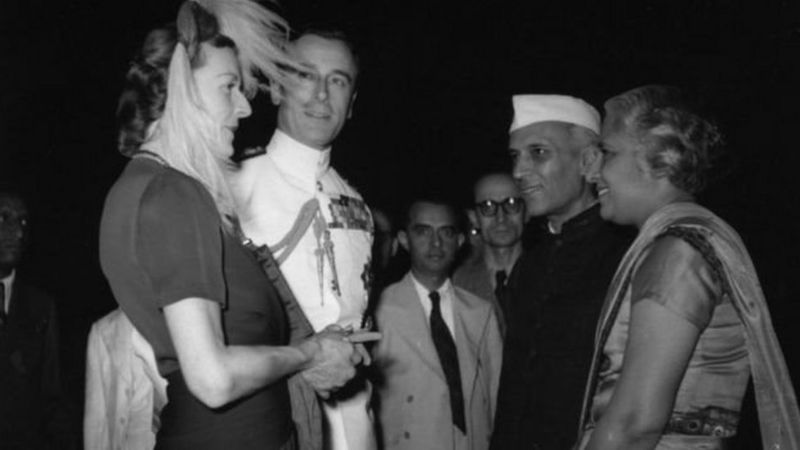

Lord Mountbatten also reiterated the recommendations of the Cabinet Mission Memorandum in his address to the Chamber of Princes on 25 July 1947. However, Mountbatten, who was a good friend of Jawaharlal Nehru and was thinking of becoming the first Governor General of independent India at the time, also told the Rajas and Maharajas gathered there that ‘every sensible ruler would wish to be a part of a wonderful country i.e. Independent India.’

However, it became clear to the princely states that they have these options: annexation with India, annexation with Pakistan, or declaration of full sovereignty and independence.

Lord Mountbatten’s method gave the princely states very little time to make that decision, which angered Lord Listowel.

In a letter to the Prime Minister Clement Attlee dated July 29, 1947, he pointed out that Lord Mountbatten had given an ultimatum to the princely states to decide whether to join India or Pakistan before August 15, 1947. Probably, in fact, it is not in line with what was discussed in Parliament.

Lord Listowel wrote: “It seems to me that the Viceroy’s attention should be drawn to these contradictions, so as not to emphasize these points in future negotiations with the princely states. Viceroy has the status of a mediator. That is why we are accountable for his statements, so it is important to make him aware of these dangers, especially since the opposition does not want us to put any pressure on the princely states”.

On August 2, 1947, Lord Listowell sent a telegram to Lord Mountbatten expressing his and Prime Minister’s concerns.

Lord Mountbatten was informed that a government spokesman in Parliament had made it clear that it would take time for the princely states to reach a decision and that they might sign a ‘stand still’ agreement which would be accepted.

In preparation for the overthrow of British imperialism in India, the Indian Independence Act of 1947 clarified the position of the British Government that “the supremacy of the British Crown cannot be transferred under any circumstances” and that it would end. ۔ However, the Act also states that the British Government has no responsibility towards the new governments of the territories which were part of British India just before that day (August 15, 1947).

It seems that some of the provisions of the Act were needed to be further clarified, so as to know what would happen to the princely states which would not join India or Pakistan before 15 August 1947.

There is strong evidence that both Pandit Nehru and Lord Mountbatten came to know about this act as soon as it became law. Both wanted to ensure that no further additions were made to the Act and that nothing be said during the parliamentary debate to acknowledge the possibility of non-accession of the princely states

Were there any Facilitations in Indian invasion of Kashmir?

To address the issue, Mr. Menon, a close associate of Jawaharlal Nehru, was sent to London to brief the Prime Minister Attlee and deliver a “note” of Nehru to him.

This is confirmed by a letter sent by Menon to Lord Mountbatten on July 18, 1947. “Your letter and the personal note I brought with me from Nehru were sent to Downing Street (the residence of the British Prime Minister) on Sunday,” he wrote. The Prime Minister met me the next morning at ten o’clock. You taught everyone a lesson! … Then I tried to put our case before him regarding the princely states.

“He called the law officers and Henderson into the room and we talked about it for about 70 minutes. Mr. Attlee was desperate to help. We studied Article 7 and tried to come up with different recipes”.

“I also met with Lestowel, Henderson and Corpus, and all three promised that they would point out in their speeches that the Queen’s Government would not welcome the fragmentation of the newly formed kingdoms. Everyone cooperated a lot”.

In a telegram sent to Listowel on July 12, 1947, Lord Mountbatten wrote: “Any attempt to clarify the status of non-aligned princely states in Parliament, I think, would be premature and would lead to the ongoing negotiations here.” The outcome could be negative.

It is clear from this correspondence that Mountbatten and Congress worked together not to clarify the ambiguous provisions in the Indian Independence Act of 1947 concerning non-aligned princely states. It can also be deduced from this that this was done to facilitate India’s occupation of Kashmir.

On August 15, 1947, Kashmir became Legally Independent

Under the Indian Independence Act of 1947, British rule over Kashmir ended on 15 August 1947. And since Kashmir did not join India or Pakistan before August 15, it became legally independent. Maharaja Hari Singh wanted to remain independent. This was made clear by the fact that he had expressed his desire to conclude a standstill agreement with both India and Pakistan under the Indian Independence Act of 1947.

On 12 August 1947, the Maharaja sent one telegram to both the countries. Pakistan agreed to this agreement on 15 August 1947. As far as India is concerned, India was negotiating but never signed the agreement.

The signing of this agreement with Pakistan and the negotiations with India on it are a clear indication that neither of the two new countries had any authority or supremacy over Kashmir.

It is clear from all the legislation and statements of the British government that as soon as British imperialism ended in India, Kashmir became completely independent and this was recognized by both India and Pakistan. It can also be said that from 15 August 1947 to 26 October 1947, when Kashmir was annexed to India, Kashmir was completely independent.

On June 3, 1947, Mountbatten’s plan made it clear that India would be divided into two countries. The issue of annexation of the princely states was very important in the agenda of the Congress party. For this purpose, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was assigned to the Home Department and his job was to persuade the princely states to join India and he succeeded to a large extent.

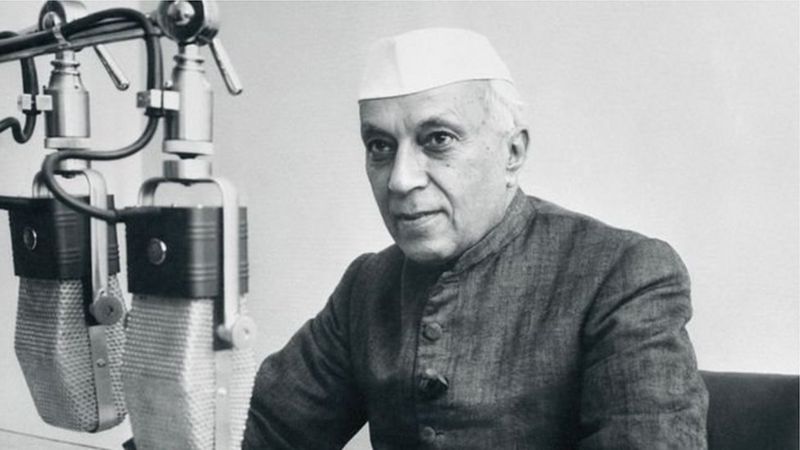

There were only three princely states that did not decide whether to join. Kashmir, Junagadh and Hyderabad Deccan. Kashmir was strategically important and at the same time Nehru had an ’emotional connection’ with Kashmir because it was the homeland of his ancestors.

Nehru’s ‘Emotional Connection’ with Kashmir

Documents from the time indicate that there was intense lobbying for Kashmir’s accession to India. This is also made clear by Mountbatten’s own remarks in his personal report No. 15 on Nehru’s emotional connection with Kashmir. “I found out that when Patel tried to persuade Nehru before meeting me, he burst into tears, saying that nothing was more important to him than Kashmir at the moment,” he writes.

It is clear that this ’emotional connection’ and close friendship with Mountbatten played a key role in the ‘intimidation and coercion’ campaign that forced Maharaja Hari Singh to join India.

To this end, Lord Mountbatten visited Kashmir from 18 to 30 June 1947, where he had several initial meetings with Maharaja Hari Singh and his Prime Minister RC Kak.

The Difficulties for Maharaja Hari Singh

1947 was a difficult year for Maharaja Hari Singh. Pressure from local parties, civil war in Poonch and above it pressure from political leaders and viceroys of British India.

A study of the documents at the time also indicates that the Maharaja had made up his mind to remain independent, which is why he avoided further meetings with Mountbatten so that he would not have to talk about accession and Let them have some more time for themselves.

However, Mountbatten persuaded the Maharaja to enter into a ‘stand still’ agreement with both India and Pakistan. Mountbatten also brought with him a ‘note on Kashmir’ from Nehru for the Maharaja. The language and tone of this note was quite aggressive: ‘The situation in Kashmir cannot be matched without major changes. If this does not happen, the Maharaja’s position will become more unstable.

However, if the Maharaja leads the Constituent Assembly of India in this direction. The immediate steps required are the removal of Prime Minister Kak and the release of Sheikh Abdullah and his associates. What happens in Kashmir is certainly very important for the whole of India. Because this border state is of strategic importance. The resources of this state are vast. If Kashmir is tilted towards the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, the result will not be good. Kashmir’s participation in the Constituent Assembly of India is natural. The tone of the note was like an order and it directed Maharaja Hari Singh to dismiss Prime Minister Kak.

According to Maharaja Hari Singh’s son, Yuvraj Karan Singh, Prime Minister Kak was “a man of mental capacity and consciousness.” He was a nationalist Kashmiri Pandit and a follower of Kashmir’s independence. Nehru believed that the refusal of Maharaja Hari Singh to join was in fact the handiwork of Prime Minister Kak and therefore wanted to oust him.

At the same time, because of his friendship with Sheikh Abdullah, Nehru personally wanted to set him free. Nehru saw Sheikh Abdullah’s party, the National Conference, as a partner of the Congress.

After Mountbatten’s visit to Kashmir, he was accused of actually campaigning on behalf of the Congress to ensure Kashmir’s accession to India. And if not annexation, at least to ensure that Kashmir does not declare independence prematurely.

Lord Mountbatten and Nehru’s Special Friendship

Sir Conrad Corfield was Viceroy Mountbatten’s political adviser from 1945-1947. In his view, Mountbatten permanently ignored the advice of the British Indian Political Department and British policy on the princely states.

According to Corfield, his advice to Mountbatten as a political adviser had no value in the face of Viceroy’s long and deep friendship with Nehru, who wanted Kashmir to remain with India. Mountbatten decided to go to Kashmir against Corfield’s advice and, contrary to popular British policy, he did not take his political adviser with him.

Corfield believed that Mountbatten did so because his friend Nehru wanted to annex Kashmir to India somehow. Mountbatten also rejected Corfield’s advice on Kashmir and Hyderabad. Corfield had suggested that the two princely states could be used as broker to compromise between India and Pakistan because Kashmir was a Muslim-majority princely state with a Hindu Maharaja and Hyderabad a Hindu-majority princely state with a Muslim ruler. However, the plan was rejected by Mountbatten.

Despite this, Nehru was not happy with the outcome of Mountbatten’s visit to Kashmir. In a letter to Mountbatten, he wrote, “In my view, your visit to Kashmir has not been successful. Everything is the same as before. On the contrary, I was very disappointed with the results of your visit. Kashmir had become very important to me.

After a failed visit to Mountbatten, his Chief of Staff, Lord Hastings, was sent to Kashmir. The Maharaja treated them the same way and no serious progress was made on accession. In his personal report dated August 2, 1947, Mountbatten wrote, “Nehru himself is anxious to go to Kashmir.” Mountbatten believed that Nehru could not forget the day he was arrested in Kashmir.

When Nehru was Arrested in Kashmir

On June 18, 1947, when Nehru tried to enter Kashmir in solidarity with Sheikh Abdullah without the Maharaja’s permission, he was arrested on the orders of the Maharaja in Domal and was detained for two days.

Nehru must have been shocked by this. He was a well-known leader of the Congress at the time and was seen by all as the future Prime Minister of independent India. That is, until 1947, the Maharaja had so much power that he could carry out his orders as he wished and the British government had no control over them.

After Nehru’s capture, Mountbatten contacted the Maharaja and asked him to allow Nehru to enter Kashmir. However, the Maharaja refused. A study of The Mountbatten Papers and Special Collections Database reveals that Mountbatten knew that Prime Minister Kak and the Maharaja had a “strong hatred” of Nehru.

Mountbatten also knew that the press would not take kindly to the visit of any Congress leader to Kashmir. Mountbatten suggested that “if Gandhi goes to Kashmir, his negative aspects can be minimized because of the religious color of his personality, while if Nehru does, it will be seen as clear political lobbying.”

It is clear from these documents that Mountbatten was working for the benefit of India in spite of being a Viceroy. Gandhi went to Kashmir and stayed there till August 4, 1947, during which he met the Maharaja and his entire family. It was only after this that Prime Minister RC Kak was removed from his post and replaced by General Junk Singh as the Prime Minister.

With the dismissal of RC Kak, the demand of the Congress was fulfilled just as Nehru had written in his ‘Comprehensive Note’ which Mountbatten had conveyed to the Maharaja. It is clear from the documents of the time that this created severe tension in the state.

The Maharaja was being forced to join India, as evidenced by the irregularities that appear in the work of the Radcliffe Commission after consultation with Mountbatten.

When Mountbatten found it impossible to establish a united India, he announced a transfer of power in his June 3 plan, which included the partition of Punjab, Bengal and Sylhet on the basis of two nation ideology.

Partition of India and the Radcliffe Commission: The Question of Gardaspur

On June 30, 1947, the Radcliffe Commission was formed to divide the territories. However, the commission annexed the Muslim-majority area of Punjab to Gardaspor India, giving India the only access to Kashmir. Liaquat Ali Khan wrote a letter to Lord Ismay about this, in response to which Lord Ismay wrote, ‘I am stunned to see your personal message sent through Muhammad Ali. As far as I understand, the gist of it is that … Gardaspor, The Boundary Commission has given to East Punjab. The news is that this is not a fair decision but a political decision: if it is, it is a great injustice and it would be tantamount to breaking the trust and confidence of the British.

The Radcliffe Award was unveiled only after August 15, 1947, although Mountbatten learned on August 8 that it was being given to India despite the Muslim majority in Gardaspur. India’s delay in signing the ‘Stand Still’ agreement with Maharaja Hari Singh was apparently because the leadership awaited the decision of the Radcliffe Commission.

This is reinforced by a statement by Menon in which he said, “We want time to understand the implications of the stand-off agreement. Thanks to the Radcliffe Award, the state now has a land relationship with India.

Menon’s statement suggests that ground access to Kashmir was the result of Nehru’s political maneuvering, which eventually led to the entry of Indian troops into Kashmir after reluctance to join India.

The fact is that Kashmir had become independent by August 15, 1947 without joining India or Pakistan. The partition of British India and the irregularities of the Radcliffe Commission resulted in large-scale migration of Hindu and Muslim populations, as well as massacres and killings.

Internal situation in Kashmir and Tribal Attack

By this time, political tensions in Kashmir had escalated and protesters had taken to the streets, especially in Poonch. The Maharaja’s army was accused of massacring the Muslim population of Jammu. According to some estimates, out of a population of 500,000, about 200,000 were killed and those who survived fled to Pakistan.

The result of this news was that on October 22, 1947, Kashmir was invaded by the tribesmen of Pakistan’s NWFP, with the aim of helping their Muslim brothers in Kashmir. The Pathan tribesmen came in two or three hundred trucks and started looting and killing.

The last Commander-in-Chief of United India, Field Marshal Achlenlik, was appointed Supreme Commander on September 30, 1947, a position he held until November 1947. Its purpose was to ensure the division of the armed forces between India and Pakistan.

According to Menon, when Auchinleck received advance notice of the tribal attack from the Pakistani military headquarters, he informed the Indian government.

News of the tribal invasion reached India on October 24, 1947, and the next day the Indian Defense Committee, of which Mountbatten was a member, decided that Menon should immediately go to Srinagar to seek information.

Menon, along with Colonel Sam Manekshaw, an officer in the Air Force, was sent to Srinagar in the Royal Indian Air Force’s DC III. At that time, the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army, General Frank Messervy, was in London to buy weapons for the Pakistan Army because he had no share in the arms at the time of partition.

According to Menon, India had planned to send Indian troops to Kashmir by air and land after October 24, 1947. It is clear that in this situation, instead of starting a war between India and Pakistan, joint action should have been taken by both sides against the tribesmen, especially since the Supreme Commander of both armies was the same. Field Marshal Auchinleck.

What happened after the tribal invasion shows Britain’s irresponsibility, lack of moral accountability and readiness to protect the security of the royal state of Kashmir. Kashmir did not join India or Pakistan. The protection of Kashmiris was the legal and moral responsibility of Britain.

Conditional Accession Agreement

After this tribal invasion, the Maharaja fled to Jammu on 25 October 1947 and sent his new Prime Minister Mahajan (who had been appointed to the post after Janak Singh) to Delhi for military assistance. India refused to help without accession. On 26 October 1947, the Maharaja wrote a letter to Mountbatten annexing Kashmir to India and, according to Menon, signed the “Treaty of Accession in Jammu”.

On the same day, Menon appeared in Jammu, obtained the Maharaja’s signature and promised him military assistance to restore his rule in Kashmir.

On 27 October 1947, Mountbatten temporarily accepted the accession treaty, on the condition that the Maharaja’s decision with India in Kashmir be put to a vote.

The two letters, dated 26 and 27 October 1947, the first from the Maharaja to Mountbatten and the second from Mountbatten to the Maharaja, are part of the Treaty of Accession which the Maharaja signed. In the first letter the Maharaja offered to join and in the second Mountbatten accepted the offer. These two letters together constitute an international agreement. This means that the Maharaja’s letter of accession cannot be considered complete and final on its own unless it is accompanied by a reply from the Indian Governor-General and a referendum.

One letter offers Kashmir’s accession to India and the other makes it clear that the offer was accepted with certain conditions.

According to documents preserved in the British Library, Manuscripts and European Private Papers, India feared to lose control of the region and therefore resorted to massacres to drive the Muslim majority out of Kashmir. These documents also indicate that its purpose was to ensure India’s victory in any referendum.

But when the Indian Army invaded Kashmir, it was stated on government level that its purpose was to preserve democracy and create conditions for a fair referendum. India also said that its forces actually entered Kashmir to help the Maharaja against the tribal invasion.

Author Alistair Lamb in his book Incomplete Partition. The Genesis of Kashmir Dispute writes that before the invasion of Kashmir, India had made full preparations and that Lieutenant General Dudley Russell personally supervised the plan, while Mountbatten also helped. Nehru reiterated his promise of a referendum and said that it was incumbent on India to do so.

Mountbatten was late in Proposing a Referendum

Morris-Jones was Mountbatten’s constitutional adviser from June to August 1947. Commenting on the referendum in June, he said that the referendum in Kashmir was a “thought-out option” but it was not “very important on Mountbatten’s agenda”.

And when Mountbatten finally proposed a referendum in October, it was too late, he was not a Viceroy at the time, and he did not have the authority to ensure a referendum.

On 27 October 1947, the troops of the First Sikh Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel Dewan Ranjit Singh, were airlifted to Kashmir. India then sent troops to re-capture the area of Pakistan occupied by the tribes and thus began the first war between India and Pakistan, at a time when the leadership of both armies was in the hands of British officers.

When the war ended, India occupied parts of Kashmir, including Srinagar, Jammu and Ladakh. On the other hand, Pakistan had taken control of the western part of Kashmir, which they named Azad Kashmir and whose capital was Muzaffarabad.

Opinions on the Legality of Kashmir’s Accession to India

The question of the legality of the Kashmir Accession Treaty was first raised in a telegram sent by the US Secretary of State for Southeast Asia to the British Foreign Office. Among other things, it raised the question of “how much scope will the UN Security Council have to question the legality of Kashmir’s accession to India?”

Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice was a legal adviser in the British Foreign Office. In response to this telegram, he wrote in his reply dated 25 February 1948, “I think it would be correct for the Security Council to decide that the circumstances under which Kashmir was annexed by India were a matter of law and order and security.” The threat is, and still is, the root cause, and that peace and security cannot be restored unless it is revisited.

In that case, I would say that the decision is not beyond the powers of the Security Council to reconsider the issue and the annexation of Kashmir, whether with India or Pakistan, is based solely on the decision of the Maharaja. It should be more than a decision, even if the constitution of Kashmir gives the Maharaja the right to make such a decision.

On February 27, 1948, Sir G. Fitzmaurice, in his opening remarks on the Government of India Act 1935 and then the Indian Independence Act of 1947, wrote, “It seems that if the ruler of an Indian princely state, of his own free will, Announced annexation by pressure or deception and this announcement was accepted by the Governor General of this country, then this annexation is permissible, whether or not this ruler has the authority to do so under the constitution of this princely state.

On February 27, 1948, Sir G. Fitzmaurice, in his opening remarks on the Government of India Act 1935 and then the Indian Independence Act of 1947, wrote, “It seems that if the ruler of an Indian princely state, of his own free will, Announced annexation by pressure or deception and this announcement was accepted by the Governor General of this country, then this annexation is permissible, whether or not this ruler has the authority to do so under the constitution of this princely state.

That is, if the Maharaja had decided to join India freely, of his own free will, and it had been accepted by the Governor-General of India, then the accession would have been legal at the international level, regardless. Whether the Maharaja had the authority to do so under the Constitution of Kashmir or not.

According to this theory, Sir G. Fitzmaurice concluded that if the Maharaja had decided to join voluntarily, then the accession was technically justified. However, the Maharaja was under pressure not only from India but also from Governor-General Mountbatten, and at the same time the Governor-General conditionally accepted the offer of accession. This makes it clear that the accession agreement itself is not valid for these reasons.

Considering the same issue from another point of view, Sir G. Fitzmaurice also considered the possibility of the princely states becoming independent states after the end of British rule. “It is a matter of annexation of one independent state with another,” he wrote. I think in such a case it can be said that the Government of India Act 1935, which is enshrined in the Indian Independence Act of 1927, merely indicates the process which is mandatory for annexation, but its annexation is permissible or not. The question of existence does not matter.

Kashmir’s Annexation to India is Illegal

In 1949, at the request of the Commonwealth Relations Office, Sir G. Fitzmaurice (as legal adviser to the British Foreign Office) gave his revised opinion on Kashmir’s accession to India. This time he admitted that he was unfamiliar with some facts while giving his initial opinion on February 27, 1948. Based on the new evidence, he said that Kashmir’s accession to India was in fact illegitimate.

He said, “I have been asked to give my opinion on an issue on which I have given my initial opinion last year, that is, the issue of legitimacy of Kashmir’s accession to India.” I will not repeat the facts here. However, I was not aware of some facts last year when I gave my initial opinion and in the light of these facts I have now come to the conclusion that Kashmir’s accession to India can be considered absolutely illegitimate, unless It is not known (and I do not think there is any such report) that Pakistan had so far violated its standstill agreement with Kashmir which led to the termination of that agreement.

The then British Attorney General, Sir Hartley Shaw Cross, in his letter to Fitzmaurice on June 20, 1949, agreed with three legal points of view: The Maharaja was not free at the time of accession; The second is that … The Maharaja did not have the control of the state and he was not in a position to ensure accession and the third was that … The offer of accession was accepted conditionally.

It can be deduced from the legal opinion of Sir G. Fitzmaurice that the kingdom of Kashmir did not legally end in 1947. It is clear that both Britain and India agreed to hold a referendum in Kashmir. However, since then, India has reneged on its legal obligation.

In his revised opinion, Sir G. Fitzmaurice compared Kashmir to the Baltic States and said that in the absence of legitimate annexation, it was in fact a case of annexation by force or military force.

It has been 73 years since the military-led annexation. Attempts were made to make the imperial state of Kashmir a constitutional part of India under Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution.

However, on August 5, 2019, India unilaterally repealed Article 370.