Without a doubt, this is truly exhausting. Aurat March was an extremely powerful expression of the outrage at the apathy of the government and society towards pervasive discrimination. It is just as true now as it ever was that the state will not give women anything without a fight.

Police in Lahore, the provincial capital of Punjab, have registered a case of alleged rape and looting of a woman near the motorway and have launched an investigation into the incident and arrested 12 suspects.

Special Assistant to the Prime Minister for Political Affairs Shahbaz Gil said in a tweet that the administration was busy tracking down the culprits with the help of various methods of interrogation and the CCPO Lahore himself was leading the investigation team.

According to an FIR lodged at Gujjarpura police station in Lahore, the car of a relative of the petitioner, a resident of Gujranwala, had run out of petrol near the forest and she was waiting for help.

According to the FIR, the petitioner’s relative said that while she was waiting for petrol, two armed men between the ages of 30 and 35 came, took her and her children out of the vehicle, raped them, snatched cash and jewelry and fled.

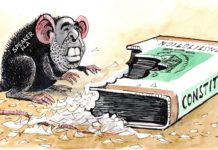

Violence against women in Pakistan is both a crime and a socially accepted norm. While we have laws that protect women from violence, the state has absolved itself of the responsibility to enforce these laws. This means that women have an inherently paradoxical relationship with the state: with one hand the state gives women rights in the form of constitutional guarantees, international treaty commitments and some progressive legislation; with the other it takes away these rights by refusing to implement these laws or take measures to create the conditions under which these rights can be realized.

Sexual assault in Pakistan is as prevalent as it is normalised. When a woman tells someone about it, the first response she usually encounters is one that tells her to stay silent because “what’s the point anyway”. Even the survivors’ families that are supposed to protect the well-being of all members of its unit often respond by adding more restrictions on the woman’s mobility instead of addressing the issue head-on. Their usual argument is that as the harm has been done, approaching the police will only exacerbate the shame.

But the fact is that when sexual assault occurs, the harm is directed upon the body and the mind of the woman assaulted. To assume that somehow the shame is shared by the family is a serious threat to justice and is just another way of cornering the survivor. To make matters worse, all this tiptoeing combined only goes to embolden sex offenders.

However, when it comes to effectively protecting women against sexual violence rooted in patriarchy, however, these same state authorities become either apathetic or complicit. This is not to say that formal equality is insignificant. It is crucial in a context where social and cultural norms relegate women to subservient roles and render them highly vulnerable. It is valuable particularly in view of the fact that there was a time in Pakistan’s history when discrimination against women was official state policy. During Gen Ziaul Haq’s era, the state pursued an active agenda to preserve the subservient status of women. This period saw the enforcement of discriminatory policies and the imprisonment of women under Hudood laws.

Zia’s overt discrimination against women depended on conflating the suppression of women with tenets of Islam, and the portrayal of demands of gender equality as anti-religious. This insidious discourse continues to impede the movement for gender equality long after Zia is gone, and even after some of the pernicious laws passed under his time have been substantially chipped away. The association of equal citizenship of women with an ‘anti-Islam’ agenda continues to haunt the women’s movement. The fact that today the slogan ‘mera jism, meri marzi’ (my body, my right) is deemed an insult to the religious and cultural values of the country is, in part, a result of Zia’s legacy.

This begs the question: do policies and programmes exist to allow the state to portray an image of being ‘woman friendly’ while avoiding responsibility for taking truly effective measures? Are these measures really just smoke and mirrors, intended to deflect attention away from the unwillingness of the state to challenge patriarchy by taking effective measures to end sexual violence against women?

One news after another in Pakistan. Rape and murder of a five-year-old girl in Karachi. A woman is gang-raped in front of her children on a motorway in Lahore. So is Pakistan safe for women? When it would be safe for a woman to travel alone, live alone, and breathe alone? This is the basic right of being citizen. When will the patriarchy allow women to practice this? Women in Pakistan feel frightened and angry. This is the price they pay for simply existing as a woman.