Farmers in India are on a nationwide strike on Tuesday in protest of reforms introduced by the central government in the agricultural sector.

Farmers have been protesting since the introduction of ‘market-facilitating’ laws in the agricultural sector in September, and for the past 12 days, thousands of them have been entering the capital, Delhi. There are sit-ins on different main routes connecting the country.

The majority of farmers are from the northern states of Punjab and Haryana and are the richest agricultural communities in the country. This campaign has garnered the support of Indian Punjab and overseas Indians on social media.

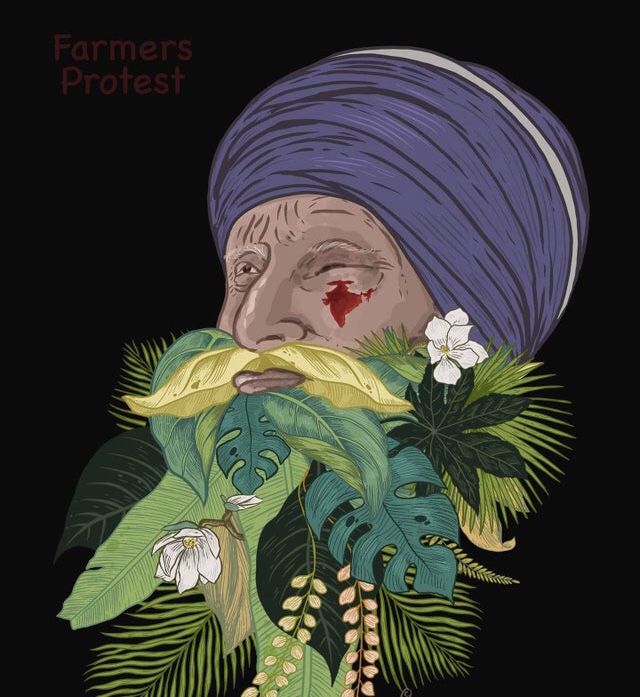

Punjab and Haryana are considered to be very important for the supply of food in India and images circulating over social media over the use of tear gas and water cannons on the elderly farmers here in the severe cold have garnered tremendous public sympathy and angst.

The strike was called after several rounds of talks with the government failed. The next round of talks is expected on December 9.

The farmers ‘strike has been supported by 24 different parties in the country, while the government says the opposition has no other issue to play politics, so they have jumped behind the farmer’s veil.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is of the view that these reforms, which allow for a more private role in the agricultural sector, will not affect the income of farmers but is for their benefit. But the farmers do not agree with their words and arguments and thousands of them from different states of India decided to register protest by marching on foot and on tractors towards the capital New Delhi.

Indian farmers gathered at the historic ‘Ram-Leela’ ground to record their protest but the government prevented them from entering Delhi and allotted a place for them but the farmers refused.

According to farmers’ organizations, so far they have the support of a total of 24 parties for the December 8 strike. However, they have appealed to all supporting political parties not to use the movement politically.

Justifying the demands of the farmers, the main opposition party Congress and the allies have fielded strong local political parties at the regional level – DMK, TRS, SP, BSP, RJD, Shiv Sena, NCP, Akali Dal, Aam Aadmi Party, JMM and Gupkar Ittehad have supported ‘Bharat Bandh Movement’ (Shut Down India).

Speaking to the media on Monday evening, Darshan Pal Singh, president of the Kisan Union (Revolutionary), said: “We thank all the political parties for supporting our demands, justifying them. But we will appeal to them to leave their flags and banners at home and support only the farmers when they come out in support of ‘Bharat Bandh’ on Tuesday. ”

Meanwhile, the Home Ministry on Tuesday directed all states and central regions to maintain law and order and keep restraint during the ‘Bharat Bandh’. It also instructs to follow the guidelines of Covid-19.

What do these reforms say?

These controversial reforms will soften existing rules regarding the sale, price and storage of agricultural commodities. Indian farmers have been protected from the forces of the free market for decades because of these rules.

The new rules also allow private buyers to stockpile goods for future sales, which previously could only be done by government-approved agents. In addition, they have established contract farming rules in which farmers can change their production keeping in view the demand of a particular buyer.

The biggest change is that farmers will be able to sell their produce directly to the private sector (agribusiness, supermarkets and online shopping websites) at market prices. Most Indian farmers currently sell most of their produce in government-run wholesale markets at subsidized prices.

These markets are run by market committees which include farmers, big landowners and traders or ‘commission agents’. The job of these agents is to act as a middleman for the sale of goods, to manage storage and transportation, and even to negotiate. At least on paper, these reforms allow farmers to sell their produce outside the market system.

So why the outrage among farmers?

Farmers are uncertain about what will happen after the implementation. Gurnam Singh Charuni, one of the movement’s central leaders, said: “If you allow big business to set prices and buy goods, we will lose our land and our income.” “We don’t believe in big business,” he added. Free markets operate in countries with less corruption and more regulation. They are not applicable to us here in India.

Farmers worry that the reforms will eventually lead to the elimination of wholesale markets and support prices, leaving them with no recourse. This means that if they are not satisfied with the price offered by a private buyer, they will not be able to go to the market and sell it, nor will they be able to bargain with the buyer based on the market price.

The government says the market system will continue and will not take back the current support prices, but farmers are skeptical. Multan Singh Rana, a farmer from Punjab, said: ‘The first farmers will be attracted to these private buyers because they will offer better prices. Government markets will close again and after a few years these buyers will start exploiting farmers. That is our fear”.