It was a dark night in mid-November 1582. A boat landed at the port of Algeria, Sardinia, and saw the city for the last time.

The ill-fated man is said to have come from Marseilles, 412 km across the Mediterranean. There had been an epidemic for a year and it looks like he brought the epidemic with him. He had delirium and swelling in his groin (the middle part of the abdomen and thigh) which was said to be characteristic of Boboz disease.

And somehow he escaped from the sight of the inspectors on duty at the seaport (who were on duty to stop anyone with symptoms of the disease) and entered the city. He died a few days later and the epidemic began there.

By this time many of the inhabitants of Algiers had fallen ill. Citing official records of the time, an 18th-century historian estimated that the epidemic killed 6,000 people and left only 150 alive. The disease is said to have actually killed 60 percent of the city’s population. A large number of mass graves have been excavated which are still standing today. About 30 people were buried together in these long and deep graves.

However, the situation could have been worse. Most of the surrounding districts somehow survived. Unusually, the disease remained in Algeria and disappeared in eight months. It is said that all this happened because of the far-sightedness of one person and his social distancing suggestion.

“It was amazing to have such a wise head in a small local town,” says Benedict, professor of history at the University of Oslo. In large commercial cities such as Pisa and Florence, you can expect the measures to be more stringent. But that man was ahead of his time. It’s very impressive. ”

Hens and urine

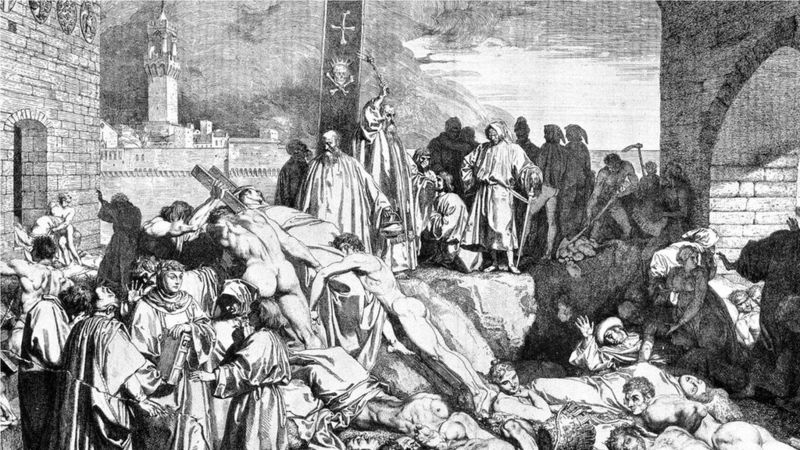

The most notorious plague in history was, of course, ‘The Black Death’, which spread throughout Europe and Asia in 1346, killing an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

In Florence, the Italian poet Francesco Petrarca, never imagined that future generations would understand the scale of this catastrophe. He writes: “O fortunate generation, who will not face such unfortunate misfortune and will see our testimony as a fairy tale.”

The remains of plague victims are still found today as we begin projects where tunnels have to be dug, such as the Cross rail project in London. Records show that about 50,000 bodies were found under Farringdon station alone.

Although the plague never became so devastating again, it continued to occur regularly for centuries to come. Until 1670, it reportedly came to Paris every three years, while in 1563 it is thought to have killed 24% of London’s population.

There was a time before modern science when it was believed that diseases were caused by ‘bad air’ and vinegar was considered as the best antiseptic. The treatment of plague was such that you would hate it, such as bathing in your own urine, etc. A common way to get ‘poison’ out of a gland was to rub it on the back of a hen.

The knowledge of the plague

As Benedict and his co-authors point out, Algeria itself was not a city ready for an epidemic. The city’s sewage system was poor, there were very few doctors and they were also poorly trained and had a ‘backward’ medical culture.

And then there’s the 50-year-old Quinto Tiberio Angelirio from the upper class. He was trained abroad because there were no universities in Sardinia at the time. It was the good fortune of the people of Algeria that Angelirio acquired his medical education from Sicily, where the plague broke out in 1575.

Angelirio’s first patient had glands and then two women with specific wounds on their bodies, another feature of the disease. Angelirio immediately understood what the problem was. The first thought that came to his mind was to ask permission to quarantine patients. But these requests were repeatedly denied. First from the reluctant magistrates and then from the Senate which rejected his report and also dismissed his concerns.

Angelirio was disappointed. “He had the courage to turn to the viceroy,” says Benedicto. “He wanted to build a three-tiered security fence around the city walls to prevent any trade with outsiders.”

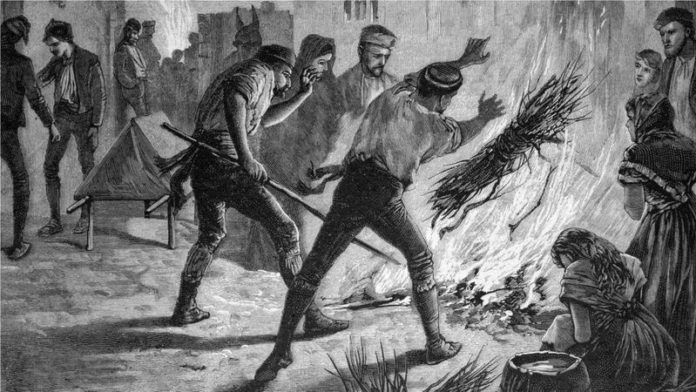

In the beginning, these measures were very unpopular and people wanted to kill him. But when more people died, they understood and Angelirio was told to do something to stop the epidemic. Many years later he published a pamphlet detailing the 57 rules imposed on the city. They were something like this:

Lockdown

The first citizens were told not to leave their homes, or to move from one house to another. In these letters, Angelirio also forbade all gatherings, dances, and entertainment, stipulating that only one person from each household would go out to shop, (a warning that is currently in effect due to epidemic restrictions. Everyone trapped will know). The lockdown wasn’t just for Algiers.

John Henderson, professor of Italian Renaissance history at the University of London’s Brubeck College, says: “In Florence, for example, they completely quarantined the city in the spring of 1631, and breaking the quarantine was really common, as it is today.

“From the summer of 1630 to the summer of 1631, I saw about 550 different cases in which people were prosecuted for various violations of public health regulations,” says Henderson. Mostly there was no complete lockdown in the city, but people were expected to quarantine themselves for 40 days if anyone in their household was suspected of having the plague and was taken to hospital. Hence the word quarantine. ‘Quaranta Giorni’. Which means 40 days in Italian.

“Obviously, people were getting restless,” says Henderson.

According to court cases, sometimes people were just miserable. For example, there was a case in which a woman had to go to jail only because she was trying to get hold of her chickens in front of the house when she was spotted by a member of the health board and arrested her for breaking the plague regulations. She went to jail but was soon released on humanitarian grounds.

In another case, a woman whose son lived in an apartment downstairs, hung a basket in which she put a pair of her socks that she wanted to give to her son. Then she pulled the bucket back up. “A health board officer saw what she was doing and sent her to jail,” says Henderson. But many did indeed commit a felony.

“Many people climbed on the roofs of adjoining houses and played guitar with friends and drank together, again breaking the epidemic rules that barred people from different places from meeting,” says Henderson. ‘

Social distancing

This was followed by a six-foot law, in which Angelirio instructed that “those who are allowed to go out must carry a six-foot-long stick.” It’s important that people keep that distance from each other. ”

Here Angelirio really emerges as an expert on social distance. Many experts did not even know it. And yet, when the epidemic of covid-19 began, many countries around the world adopted an unusually similar policy, requiring people to keep a distance of two meters (6.6 feet) wherever possible. ۔

Since then, the minimum distance has been reduced to one and a half meters in several places, including the United Kingdom, France, Singapore, South Korea and Germany. But it shows that 16th-century policy was in the right direction: one study found that the risk of transmitting the corona virus from one meter to a distance of two meters could be 10 times higher.

He added that large rails should be installed at the counters of food shops to keep people away. He suggested that people refrain from shaking hands during prayers in churches.

Wash your shopping materials

Renaissance is remembered as the golden age of classical philosophy, literature and especially art, when Michelangelo, Donatello, Raphael and Leonardo (Da Vinci) changed their fields due to their natural abilities.۔ but it was also a milestone in advancing our scientific understanding.

This was the time when physicist Nicholas Copernicus discovered that the earth revolved around the sun, not the sun that revolved around the earth, and Da Vinci planned to build parachutes, helicopters, armored vehicles and early robots. Then around 1500, leading thinkers began to work on the idea that diseases are caused by ‘bad air’, (pollution) to add to the possibility that people could get sick from touching foul-smelling or vapor-contaminated objects.

“I see a connection between the development of the Renaissance and the ability to learn more about people in the 16th century,” Benedicto said. Angelirio understood that it was spread through contact and connection. An example of this was that landlords disinfected, fortified, ventilated and “washed” their homes. He also said that anything that is not valuable should be burned, while expensive furniture should be washed, kept in the air or disinfected.

At the time, it was common for cargo to be disinfected as soon as it reached its destination, especially cargo. Alex Bamji, a socio-cultural historian of early modern Europe at the University of Leeds, says that what he thought was most dangerous was textiles. “But all sorts of things were disinfected, including letters,” she says. Sometimes they left traces behind, some of which can still be seen today. “If smoke and fire were used for disinfection, you could still find strange marks here and there.”

Health passport

One popular way to prevent the plague from spreading was to carefully examine the health of anyone who wanted to enter the city. Although the system failed in Algeria, where the ‘Patient Zero’ was evacuated in 1582 without the notice of the guards, it was still practiced in the rest of Europe.

In some cases, the authorities released documents that allowed the person holding the documents to leave the home despite restrictions, either because they had been given a plague-free certificate or he was an influential member of the society.

Philip Sloan, an associate professor of history at the University of Sterling, says: ‘So if you are a traveler and you are moving from one city to another for business or you have a plague in your city or you are going to a plague town if so, you need a health passport.

When the global epidemic of covid-19 began to spread, the concept of ‘health passport’ was reintroduced. The Common Pass is currently being tested at several international airports, including London, New York, Hong Kong and Singapore. It is a digital document that displays user test results and vaccination records. The idea is to make international travel safer and more efficient by informing the authorities of their infection status.

Quarantine

Italy is the first country to begin solitary confinement or quarantine of people suspected of being affected by the plague.

The first plague hospital, called Lazarito, was established in Venice in 1423. Soon, active patients were separated from patients who were either recovering, or who had not been diagnosed with the disease, or who had direct or close contact with plague victims. And they were socially isolated. By 1576, 8,000 older and 10,000 more patients had arrived in the city.

Then this hospital for plague patients became a model and an example of how to control the disease. These examples spread throughout Italy. This includes Sardinia, where they lived half in hospital and half in prison. Quarantine facilities were usually required there. And sometimes the patient was taken directly to the city to deal with the plague situation.

These quarantine centers were not viewed positively, people called them “hell.” Regardless of how they really were, it was probably a reaction to the thinking that was all around them. According to historians, a lot of money was spent on these centers and they were famous for their food quality.

Half of the people living in these hospitals (Lazarites) died but yes, the other half were able to go home. And that was the proportion of deaths there that could be compared to the rest of the population who were not living in quarantine facilities.

The hospitals were very well organized. The task of the plague controllers there was to keep a track record of everything that was brought in or out of these institutions. For example, bedding, furniture and food. Medical fees were not charged from the poorest members of the society. Sometimes patients were brought from their homes and orphan children were given milk and they could move around without any hindrance.

Dead cats

Despite all the similarities between the steps taken to control the epidemic in the 16th century and the way we know them today, there are some important differences. The Renaissance was also a time of superstitions and religious fallacies. It was widely considered that the plague is God’s punishment. The Church urged people to adopt the best moral attitude. Some of these instructions were not only ineffective but also incomprehensible.

Few examples of these instructions include killing a turkey and a cat and throwing them into the sea. This was surprisingly a normal practice to the epidemic. Author Daniel Defoe says that during the plague in London in 1665, the mayor of London ordered the killing of 40,000 dogs and 200,000 cats. Specialists were recruited to kill the dogs.

But killing dogs on such a large scale may have had the opposite effect. Rats were thought to be the cause of the plague. In some cities, rats were also killed directly, but this is not mentioned in Angelirio’s memoirs.

Fast forward to today, although there is strong evidence that dogs and cats can be infected with corona, these pets are just as dear today. Organizations working for their welfare say there has been a record increase in pet acquisitions in recent months. According to the RSPCA, one such organization in Australia, it has received 20,000 such applications since the onset of the coronavirus epidemic.

According to Benedict, the comparison between the ancient plagues and Covid-19 should be viewed with some skepticism. He says the plagues were worse than ever before and that there were an incredible number of deaths.

So what happened to the residents of Alghero? The plague lasted for eight months, and then for 60 years the plague did not return. But when that happened, they first turned to the instructions of Angelirio.

During the epidemic of 1652, medics followed his instructions in the letter, which included quarantine, isolation, sanitization of goods and houses, and the establishment of a sanitary siege around the city.

An unfortunate sailor who reached Alghero about four and a half centuries ago may have spread the plague, but he did something else. And it was a comprehensive guideline for hygiene and social distance for those who came after their time.